Mini-grid development and management in Nigeria: there is a need for deeper community engagement

Unico Uduka and Temilade Sesan write in our latest blog about the need for greater and deeper community engagement in Nigeria in developing new mini-grid projects.

Mini-grids are proliferating in Nigeria. SIGMA Project research photo

With over 80 million Nigerians lacking access to electricity, the national government has identified and prioritised mini-grid development as a major route to increasing electricity supply, particularly in underserved and unserved rural communities. This drive derives in part from a broader international consensus around the utility of mini grids for helping emerging economies realise their energy transition goals, especially when compared with the far higher levels of investment required for conventional grid expansion. In 2017, the Rural Electrification Agency (REA) identified about ten thousand mini-grid sites in communities across Nigeria with a total capacity of 3000 megawatts for possible development by 2023.

The government’s target of 3000 megawatts (MW) by 2023 will likely not be met, given that the total installed mini-grid capacity across the country currently stands at 2.9 MW. Nonetheless, mini-grid deployment in the country is growing at a fast clip, with several communities playing host to mini grids that mostly run on a hybrid of solar and diesel power and, to a lesser extent, biomass and hydro. While it is important to pay attention to technical details such as variations in technology and energy source, mini-grid projects are not likely to be viable or sustainable in the long term unless they build on the existing capacities and resources of key stakeholders at the community level.

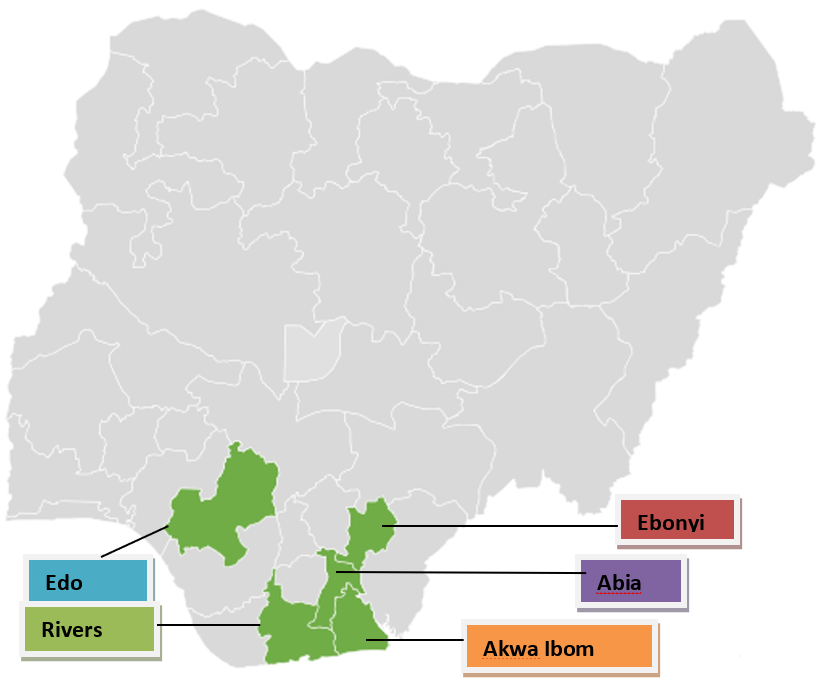

As part of the UKRI-funded SIGMA project, our research team conducted fieldwork in five communities in the south east and south-south zones of Nigeria, a region which comprises people-groups with similar (though not identical) social and cultural identities.

Map of Nigeria highlighting the SIGMA study areas in the south east and south-south zones.

Overall, the research team conducted 106 interviews and focus group discussions with community authorities, household energy users and small business owners across the study communities. A key aim of the study was to evaluate the extent to which inclusivity was embedded in mini-grid project implementation in each community: which user groups were involved, and at what stages of the project cycle; the modes of community engagement employed by external stakeholders, and the depth of engagement; and the outcomes as seen from the perspective of different user groups. This element of inclusivity is of particular interest in the Nigerian context, given that the country’s much-lauded Mini-grid Regulation of 2016 stipulates that developers invite communities to participate in the pre- and post-development phases of mini-grid development, including giving communities access to their financial accounts to enable transparency in tariff adjustments.

Community engagement: an underwhelming scenario

Our findings regarding the performances of community engagement by mini-grid developers in Nigeria reveal an underwhelming picture. While there is evidence that various groups across the study communities were indeed involved in some form of consultation with private developers prior to the installation of their respective mini grids, closer scrutiny reveals that the engagement conducted by many developers was more superficial than substantive. In many cases, the developers focused on promoting the value-addition of electricity to community members they viewed as prospective customers rather than seeking to understand their context-specific needs and capacities from the outset. Only when some projects fell short of initial projections did developers begin to tailor their approach to the needs of specific users, especially small business owners - again, with mixed results.

In compliance with the prerequisites for obtaining regulatory approval, the developers conducted feasibility studies to evaluate load capacity and establish communities’ willingness and ability to pay for the electricity that would be generated by the proposed mini grids. However, important details regarding the construction, operation, maintenance and costing of the mini grids were not effectively communicated to the prospective users.

Tariff trouble

According to the 2016 Mini-grid Regulation, tariff setting is the shared responsibility of developers and communities. Our findings however indicate that this has not been the case in practice. The regulation requires that every agreement between a community and a developer be formalised with a signed contract which specifies the tariff; however, the transparency with which this has been done in the study communities is not clear. In one case, community members claimed to have no knowledge of the terms of their contract or the entities that signed on their behalf, even though their mini grid has been in operation for two years.

Substantive community engagement can help external stakeholders to better understand user needs and capacities. SIGMA research photo

While other communities indicated that they were aware of the proposed tariff prior to signing on, they realised in retrospect that they did not fully grasp the concept of tariffs at the time, neither did they comprehend the ramifications of their commitment to it. Those ramifications become apparent when we consider that some mini-grid users in the study communities pay up to five times as much for a unit of electricity as the highest-paying grid customers in the region. This is the case despite the reality that incomes are generally higher in grid-connected areas than in the unconnected regions targeted by mini grids. Even in cases where mini-grid subscribers were fully aware of the tariff implications at the outset, they have not been involved in subsequent discussions to raise tariffs as required by the 2016 regulation.

Exploiting energy poverty?

The common thread across the communities involved in our study is that they have never been connected to electricity despite having existed for several decades. This is by design: the whole of the government’s mini-grid expansion strategy is hinged on delivering electricity to communities that are currently unserved and are unlikely to become candidates for grid expansion for the foreseeable future. This seemingly considerate provision seems to have had the unintended effect of putting those communities in a vulnerable position: precisely because they lack options and are desperate to get access, they are often not in a position to engage critically with developers and other actors who approach them with offers to transform their lives with mini-grid power.

Our findings indicate that, when executed with minimal attention to power dynamics that privilege developer interests, mini-grid arrangements can leave communities in a weak position where they are expected to be satisfied with the crumbs that fall to them. In one telling example that emerged from our interviews, a community leader was reprimanded by a developer for complaining about frequent power outages from the mini grid when, in his opinion, the community should be grateful for the modicum of access they were getting. In a similar vein, developers discount the land donations they got for mini-grid installation in some cases as a price that communities have to pay for their own progress, rather than viewing it as a sacrifice on the part of community members that should be incentivised in some way, for example, through tariff reduction.

Conclusion

We have shown through our empirical study of five mini-grid projects in Nigeria that, despite the regulatory rhetoric around inclusivity on such projects, community members are still largely excluded from substantive aspects of decision making and implementation that are essential to their long-term viability and sustainability. This is a missed opportunity for all stakeholders, as there is evidence from other contexts that integrating communities (especially those in rural areas) into the process of mini-grid development fosters a sense of local ownership and improves the functioning of projects in the long run. The cursory modes of community engagement described above, if sustained, will preclude the identification of user-responsive solutions and ultimately slow demand for mini grids among target groups. There is still time to change course: our research indicates that underserved communities remain overwhelmingly optimistic about the potential payoffs of subscribing to mini grids. Ensuring that the opportunities are matched to user realities through rigorous community engagement is the way to cash in on the promise of mini grids while fulfilling the SDG objective of leaving no one behind.