Mini grid development and management in Nigeria: Sustainability and Matters Arising

by Okechukwu Ugwu, Temilade Sesan, Unico Uduka and Ewah Eleri, August 2022

Nigeria experiences a remarkable paradox, one of acute energy poverty in the midst of plenty. Despite the country’s huge energy resources, including both large and small hydropower and abundant gas reserves, many Nigerians – 44.6% of households, according to the National Bureau of Statistics – do not have access to grid electricity. The federal government privatized the state-owned Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) in 2013, in the hopes that the private sector would bring the investment needed to drive the electricity sector and provide much-needed energy to millions of Nigerian households and productive users. However, eight years after privatization, the resulting power generation companies (GenCos) and distribution companies (DisCos) are still struggling to manage the existing infrastructure.

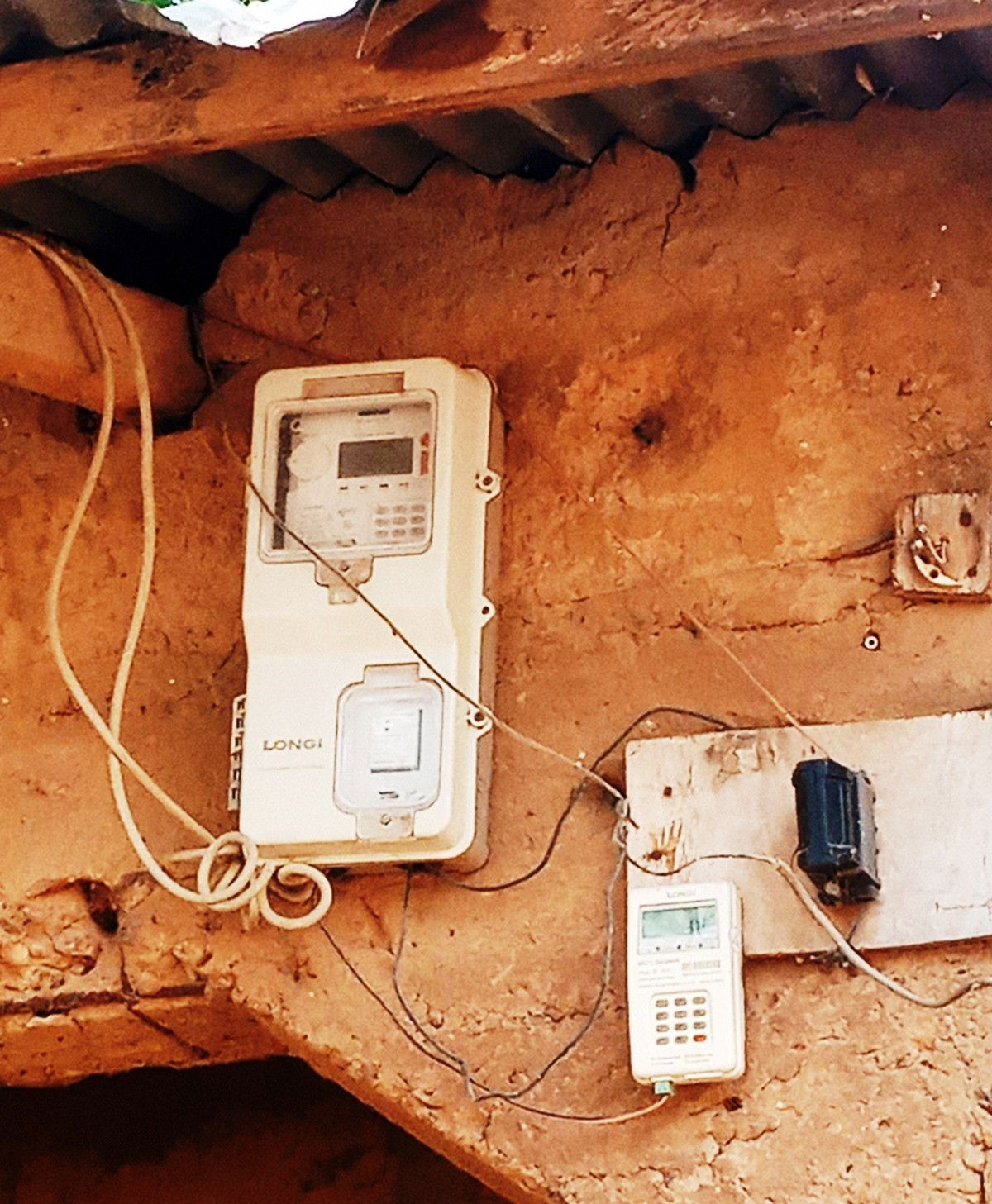

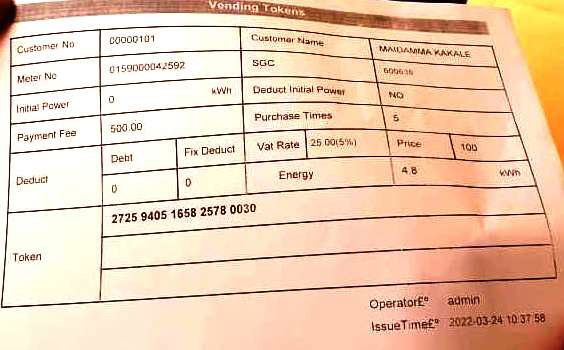

Figure 1: Prepaid meter installed in a house in one of the mini grid sites. Image: Okechukwu Ugwu, Torankawa Community, Sokoto State

Recognizing the lack of technical capacity for massive electricity development by the present operators of the nation’s electricity grid, the federal government adopted the model of providing financial support to the private sector to deploy renewable and hybrid mini grids to underserved and unserved communities and businesses across Nigeria. In this vein, several initiatives have been launched by various national and international stakeholders. Among the most prominent of these are the National Electrification Project, the Energizing Economies Initiative, the Energizing Education Programme, Nigeria Energy Support Programme, and the Interconnected Mini grid Acceleration Scheme. Today, there are over 70 mini grid sites spread across the country’s six geopolitical zones.

As part of the UKRI-funded SIGMA project, a research team from the International Centre for Energy, Environment and Development (ICEED) conducted field visits in March/April 2022 to some of these sites in northern Nigeria (see Figure 1), with the aim of evaluating their technical and financial sustainability. This focus on sustainability has become very important in light of the proliferation of mini grids across the country. To date, the majority of mini grids in the country have been financed by grants from the federal government and development partners including the World Bank, African Development Bank (AfDB) and Nigeria Energy Support Programme (EU & GIZ). For instance, the Workd Bank and AfDB funded National Electrification Project launched 57 pilot sites during its first phase. One of the main requirements for accessing these grants is the establishment of a robust technical and financial sustainability structure. Our study looked at how six mini grids in the northern states highlighted in Figure 1 have fared relative to these requirements in the time since their installation (with the exception of one long-running project, the average length of time the plants have been in operation is four years).

Figure 2: Map showing States visited in Northern Nigeria

- Federal Capital Territory (Abuja) – Rije Community, Kuje Area Council, 20 KW from biogas;

- Plateau – Nigeria Electricity Supply Company (NESCO), Buruku, 25 MW aggregate capacity from hydro;

- Adamawa – Mbela Lagaje Community, Mayo Belwa Local Government Area, 30KW hybrid mini grid (solar and diesel generator);

- Sokoto – Torankawa Community, Yabo Local Government Area, 60 KW interconnected hybrid mini grid (grid, solar and diesel generator);

- Gombe – Dakiti Community, Akko Local Government Area, 85 KW hybrid mini grid (solar and diesel generator); and

- Kano – Sabon Gari Market, 1.3 MW solar mini grid. In all, the team conducted 70 interviews and focus group discussions with community authorities, household energy users and business owners across the study communities and sites.

Technical sustainability is in limbo

First, a lack of experienced resident technicians to manage the mini grids was quite prevalent among some of the sites visited. With the exception of NESCO and the Sabon Gari Market installation being managed by Solar Power Holdings which have full onsite technical personnel, the other sites do not have skilled resident technicians. The operator managing the site in Gombe State, Leading Diagonals Engineering Nigeria Limited, has attempted to maintain presence by recruiting a couple of community members to support in managing the system. However, they are largely low-skill workers who only received crash course from the operator on basic maintenance and troubleshooting. The systems in Sokoto, Adamawa and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) are completely without operators, and the locals trained by the developers are unable to undertake comprehensive maintenance and troubleshooting. Presently, these systems are either not working or grossly underperforming (delivering far less than the installed capacity). The system in Sokoto has been underperforming since October 2021, the one in Adamawa has been delivering only 15 minutes of electricity daily since April 2021 while the system in FCT has not been functional since August 2021. The situation in these sites illustrates a key weakness in the design of mini grids in Nigeria, which is that projects are often undertaken without consideration for long-term onsite technical management.

Beyond the issue of resident skilled personnel, problems with technical designs were very noticeable in some of the sites. Apart from NESCO which has continued to sustainably maintain its systems for close to a century, the mini grids in the study have varying degrees of design deficiency. A promising mini grid design requires careful estimation of the projected load increase in the short, medium and long term. In five of the sites visited, the systems are either undersized in relation to existing load, sized based on the existing load or sized with allowance for a marginal increase in load. There is apparent scant regard for possible increases in load in the medium to long term. Take the case of the storied Sabon Gari Market: it has been in existence for decades, and the management is well aware of the composition and size of the businesses operating there. Notwithstanding these advantages, however, the mini grid design does not meet the need of existing businesses much less make provision for future load increases, keeping some businesses reliant on inefficient diesel and petrol generators.

In addition, a couple of sites are facing acute challenges with maintenance and repair. As one of the measures to ensure technical sustainability, it is good engineering practice to have a ready source of spares and inputs. This is not the case with the sites in Sokoto and the FCT.

In Sokoto, the system uses 2-volt, 600-amp batteries which are not readily available in the Nigerian market. Now some of the batteries are depleted and require replacement, making it difficult for the managers of the plant, who are locals and have no access to international markets, to source components as and when needed. This, in turn, is partly responsible for the status quo of the mini grid operating below capacity.

The system in the FCT is facing a similar challenge, albeit only in relation to proximate markets. The mini grid is powered with biogas generated from chicken droppings. The system has not been operational for over six months due to a lack of feedstock. When the project was conceived, the developer (Ajima Farms) gave the community-appointed managers the responsibility of sourcing the required feedstock. In reality, however, the feedstock is not readily available in commercial quantities in the locality, leading to a gaping shortfall in inputs.

Financial sustainability is also threatened

In addition to technical problems, we found several challenges with the financial sustainability of all the sites we visited. Again, only NESCO in Plateau and the site in Sabon Gari Market can be said to be maintaining some level of financial sustainability. These sites generate just enough income to service and maintain their existing infrastructure and personnel.

Generally, cost-reflective tariffs for mini grids in the country are higher than the rates charged for grid electricity. This is because the installation cost per KW of mini grid is higher than that for large grid systems. Ideally, mini grids should be sited in locations that guarantee financial sustainability. Nigeria’s Mini grid Regulation of 2016 stipulates that isolated mini grids should only be sited in unserved areas, which are primarily rural areas with low purchasing power. Therefore, with the exception of a few sites, rural areas are where majority of mini grids in the country are located. This puts mini grid developers and managers in a double bind: setting market-rate tariffs to enable cost recovery can lead to inability to pay among their mostly low-income customers, while reducing tariffs to accommodate and retain those customers jeopardizes the financial sustainability of their schemes.

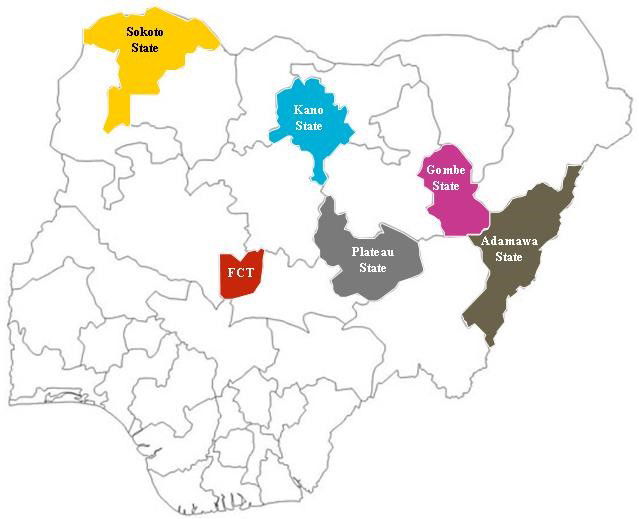

We found a typical example of this dilemma in Torankawa, Sokoto, where the cost of electricity from the mini grid is $0.25/KWh. The gross revenue from the plant stands at a maximum of $363 monthly, while the net revenue is about $121. Barring any unforeseen expenses, the mini grid would have generated net revenue of $8,700 in six years. This time frame represents the useful life of the battery bank. Meanwhile, estimates of the cost of replacing the battery bank stands at over $24,000. It therefore follows that the revenue generated cannot finance the replacement of the battery bank. Without external support, the mini grid may become non-operational when the batteries become exhausted.

Figure 3: Receipt of electricity purchase in Torankawa, Sokoto State

The situation in Torankawa is quite mild when compared to that in Mbela Lagaje, Adamawa. Here, no tariffs were charged from the time the system was installed in 2020 so the community got the impression that the electricity was free, and the developers did nothing to indicate otherwise. Four years down the line, the installation is almost non-functional due to technical issues, supplying only 15 minutes of electricity to the community every day. There is no provision on the ground for carrying out maintenance and repairs on the plant, and there is currently no hope of the community getting external support in this regard.

What the future holds

While mini grids are helping to fill the energy access gap across Nigeria, the market cannot be said to be commercially viable. Based on feedback from the field visits, a number of operators have made significant, though inadequate, efforts to ensure sustainability. A radical change in approach is needed to facilitate the technical and financial sustainability of mini grids in the country.

The current practice where the deployment of solar mini grid electricity is largely seen by some government authorities as a social intervention rather than a commercial enterprise is a limiting factor. Interviews with some government stakeholders indicate that the primary concern is increasing access to electricity rather than building business models. While it is very important to extend electricity supply to unserved and underserved communities, it is also equally important to consider long term sustainability.

Figure 4: Mbela Lagaje Community, Adamawa State

As earlier stated, the cost per KW of mini grid electricity is significantly higher than conventional grid electricity. As part of our study, we interviewed a key operator whose organization has adopted a social enterprise model in which mini grid tariffs are deliberately kept low in order to increase affordability and maximise reach in the project community. The rationale underlying this approach is that most rural communities that qualify for mini grid intervention per the dictates of the Mini grid Regulation are not inherently profitable. If this is the case, the argument goes, public funds will be needed to subsidise the cost of mini grids in the same way that grid electricity has been subsidised in the country for several decades. While this is a valid argument, the chances of it being actualised in the current fiscal and political climate are quite slim. A more immediate, albeit limited, strategy could be to emphasize the co-benefits for productive users in mini grid project design and regulation. This is because getting significant numbers of productive users onto mini grid networks, if done in an inclusive way, can boost revenue generation and increase the chances of achieving financial sustainability.

Finally, it is imperative to note that the federal government and development partners have made very serious commitments to grow the mini grid sector, as have private sector actors. However, a higher degree of coordination is required among government stakeholders if the sector is to advance at the required pace. The situation today is that various government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) are involved in mini grid development and financing without regard for what others are doing. Further, there is no standardized pricing structure for cost per KW: similar capacities within the same region are priced differently depending on the MDA promoting it. This leads to disparities in pricing, making it difficult to conduct a reliable cost-benefit analysis. Should the current trend continue, Nigeria may well get to a point where mini grids become significantly overpriced and prohibitive for target populations in rural communities. A coordination platform and a standardized costing template would help the sector to adequately understand the real cost of mini grids. Such a template, if well developed, could even help developers make projections on the viability of potential mini grid sites.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Lucy Baker for providing insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article.